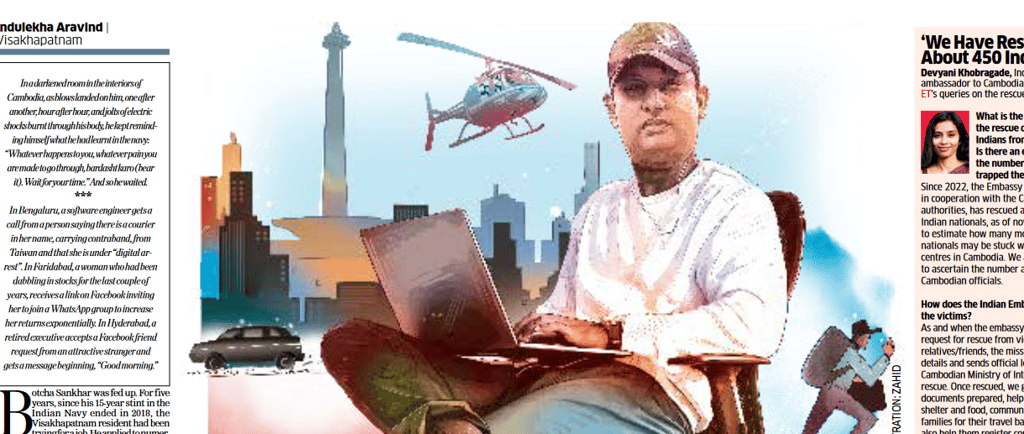

The man who escaped the scam rings of Cambodia

Thousands of workers are trafficked to Southeast Asia to commit cyber fraud by befriending and then swindling compatriots over Facebook and WhatsApp. Ex-serviceman Botcha Sankhar, who was forced to work in the scam compounds of Phnom Penh for six months, unravels the modus operandi of this new and terrifying form of crime and forced labour

8/2/202413 min read

Originally published in The Economic Times on June 2, 2024

Indulekha Aravind | Visakhapatnam

In a darkened room in the interiors of Cambodia, as blows landed on him, one after another, hour after hour, and jolts of electric shocks burnt through his body, he kept reminding himself what he had learnt in the navy: “Whatever happens to you, whatever pain you are made to go through, bardasht karo (bear it). Wait for your time.” And so he waited.

***

In Bengaluru, a software engineer gets a call from a person saying there is a courier in her name, carrying contraband, from Taiwan and that she is under “digital arrest”. In Faridabad, a woman who had been dabbling in stocks for the last couple of years, receives a link on Facebook inviting her to join a WhatsApp group to increase her returns exponentially. In Hyderabad, a retired executive accepts a Facebook friend request from an attractive stranger and gets a message beginning, “Good morning”.

***

Botcha Sankhar was fed up. For six years, since his 15-year stint in the Navy ended in 2018, the Visakhapatnam resident had been trying for a job. He applied to numerous private companies, attended job fairs for ex-servicemen and, to upskill himself, the former chef completed courses such as fire and safety. But each time, he went up against a wall. “They would ask me what experience I had in fire and safety, discounting my Navy experience completely. Or, there would be 2,000 ex-servicemen applying for 10 jobs. Or, they would judge me on the basis of my caste,” says Sankhar, who belongs to Relli, a scheduled caste in Andhra Pradesh. Dressed in a collared t-shirt and jogger pants, with a cap pulled down to his forehead, the 41-year-old speaks deliberately.

In desperation, he paid Rs 6 lakh to an acquaintance who promised him a job in the dockyard. After being strung along for months, that too, came to naught, as did an attempt to go to Poland. That’s when a relative approached him with an opportunity – a job in Singapore, either as a fire and safety officer or a data entry operator for a good salary. In return, he says, he coughed up Rs 3 lakh to an agent and a sub-agent.

In May 2023, a month before his son’s 9th birthday, Sankhar boarded a flight to Bangkok, hopeful that his search was finally succeeding, which would also help repair strained relations at home. It was only on landing in Thailand that he realised that the ticket for his connecting flight was to Cambodia, not Singapore. He immediately called his acquaintance, N Tirumala, asking what was happening. “But Tirumala told me not to worry about anything and to take the flight to Cambodia since he was already there,” he says.

At the airport in Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia, he was taken to an office by an agent, where he was made to do a typing test. The first day itself, he says, he did the rounds of six companies and, on the second, about 10 companies until, finally, he was told he was selected. In the “office”, he recalls, there were people from various states in India and some from other South Asian countries, all seated around terminals, with desktops and phones. After several days, Sankhar was assigned his task: to create fake profiles of women on Facebook which would be linked to fake email IDs and numbers.

Unknown to him, Sankhar had been sold to the company by his agent. He was now one of the thousands of workers who are illegally trafficked to Southeast Asia’s “scam compounds” to perpetrate cyber fraud to the tune of billions of dollars. They work under duress, often on their countrymen and women back home – a new form of slavery.

Why Cambodia?

The emergence of Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar as a hub of internet scams can be traced back a couple of decades, when criminal gangs from China relocated to those countries to set up illegal online gambling operations targeting the mainland, says Jason Tower, country director-Burma at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP). The USIP, an institute founded by the US Congress working on global security, terms the transnational scams emanating from Southeast Asia “a threat to global security” in a new report. The annual value of funds stolen by these syndicates, it says, amounted to a staggering $64 billion in 2023.

The online gambling started morphing into outright fraud around 2018, pioneering a sophisticated scam called pig-butchering, where trust is built with victims online over many days, before defrauding them -- akin to fattening a pig before slaughter. “Once you have established a friendship or a romantic interest, you introduce the victim to an online cryptocurrency trading platform, which you use to steal massive amounts of funds. You basically wipe them out. And then the platform is taken down, leaving them victimised at two levels,” says Tower on a Zoom call.

When China recalled its citizens when the pandemic began, the gangs pivoted from gambling to online frauds. To run operations, they turned to forced labour, even kidnapping people in some instances. The criminal groups from China are able to operate with impunity from vast, heavily guarded compounds or special economic zones close to the border by building very close ties with the ruling elite of the three countries, according to USIP’s report.

While initial targets were residents of China, this changed from 2020 due to a string of events, from a ban on cryptocurrency in the mainland to a crackdown by Chinese law enforcement to a massive awareness campaign about fake job offers that end in forced labour. As China became less accessible -- both as a source of labour and the target of scams -- the gangs took their operations global, including to India. The Indian Cyber Crime Centre (I4C) estimates that close to half the money lost to cyber fraud from India between January and April this year was siphoned off to scam centres in Southeast Asia. Rs 1,750 crore is estimated to have been lost in this period alone, ET reported earlier.

“Given that India has a highly educated population and an established tech sector, there's good reason why criminal actors would be targeting people there for access to a supply of labour as well as another market for perpetrating the scams,” says Tower. An August 2023 report by the Office of the UN High Commission for Human Rights estimated that at least 120,000 people in Myanmar and 100,000 in Cambodia were being forced to operate these cyber scams while the USIP report says these victims of forced labour, “along with a small number who willingly participate” come from over 60 countries. In March, The Indian Express reported that 5,000 Indians were similarly trapped in Cambodia, according to the Union government, though this might be an underestimation, considering many are also transported across land borders.

Sankhar might not have had a tech background but his desperation for a job had, unwittingly, ensnared him.

Reeling Them In, Slowly

The operations in the offices Sankhar was part of were very organised. To go from one floor to another, workers needed permission. “Trainees” like him had to wear yellow lanyards, while those seated at tables wore red. At a table of 16, four would be tasked with sending Facebook requests from fake profiles to befriend unsuspecting strangers. A few would be part of a dummy WhatsApp group where they would talk about how they had earned huge returns—to impress “the client” who is added to the chat group. One scam involved paying the client various amounts for “rating” a product. Soon they would be informed of “special offers” where they would get handsome returns for small investments.

Gradually, they would be convinced they could earn much more by paying bigger sums. Once they paid, they would find themselves locked out of the app they were introduced to and unable to access their own funds. All of this was supervised by Chinese managers with Malaysian translators, says Sankhar. At another office he was taken to, Sankhar says he was given a “seven-day script” to learn, detailing what to tell a client each day— to trap them. Each team member was also given 20 phones to create 20 Facebook profiles linked to fake Gmail and Telegram accounts, using pictures of good-looking women downloaded from public Instagram profiles. Each person had to send 100 Facebook requests through the day and at least three had to be accepted and converted to WhatsApp members. In case a suspicious client wanted to call, the phone would be handed over to a woman in the group. Those who did not meet targets would not get meals and their pay would be cut. One of them, Sankhar recalls, wasn’t able to eat out of guilt for having driven a “client” to death by suicide—his widow had sent pictures and videos.

But for those who cooperated and hit targets, there were rewards and incentives -- from cash to alcohol to drugs. There were also parties, with flashing neon lights, music, booze and prostitutes - for a price. “Whatever you earned could get spent there,” says Sankhar, showing a couple of short video clips. Tirumala, his acquaintance, ended up becoming an agent himself, getting his wife to send new victims over.

The scale and sophistication of these operations set them apart from earlier versions of cyber fraud, including in India. Other common modus operandi include accusing victims of receiving contraband or telling them their funds were used by terrorists, crypto scams and investment scams.

Scamsters prey on victims’ fear, says NS Nappinai, senior advocate of Supreme Court and founder, Cyber Saathi. They try to scare people with claims of the target’s child being arrested or the target being summoned by police for alleged violations of law. The data to target victims is easily available, she adds. “At how many places do we share our mobile numbers and email IDs? It’s very easy and inexpensive to get this data, even bank details.” Since these are sophisticated scams where victims are taken in over a period of time, the criminals prefer to use fellow citizens. “They need to know what script to use and also have a degree of cultural understanding —they need to really bond with the victim. That’s why they use Thais to scam Thais and so on,” says Tower. “It’s more effective.

Rescue & Return

On the evening of May 24, a Friday, the Arrival terminal of Visakhapatnam airport was unusually crowded, with a throng of journalists and a strong deployment of the city police. Finally, around 18:30, they emerged – a group of young men, flanked by Commissioner of Police A Ravi Shankar and Joint Commissioner Fakkeerappa Kaginelli. After about three hours, the next batch of 17 landed – all of them natives of Andhra Pradesh, who had been stuck in Cambodia.

One of them, Arun Reddy (name changed on request), was a 26-year-old who had finished his BSc in computer science and was promised a data entry job with a salary of $800-1,500 in Bangkok by an agent, who took Rs 1.5 lakh. Reddy says he refused to work when he realised what the job was and was beaten and starved. Another returnee, Sharath Ram (name changed), had been an insurance salesman in Visakhapatnam and was lured with the promise he could earn twice or thrice his salary. “I had to chat with men and lure them using photos of girls, and then hand them over to the Chinese. When I told them I wanted to go back, they said I would have to pay Rs 4 lakh, which I didn’t have,” he says.

The group managed to return thanks to an initiative by Ravi Shankar, who circulated a message in the news media and social media asking those who might be stuck in Cambodia to reach out to the embassy, complete with phone numbers and other details, following a detailed police complaint by Botcha Sankhar. Seeing this, a group of Indians staged a protest against their managers, contacted the embassy, got the help of local police, scrimped together money for tickets and made their way back. This was the first batch of an estimated 300. All of them, police commissioner Shankar underlined in an impromptu press conference that night, would be treated as victims, not perpetrators.

The previous evening, in his office, the commissioner said that following Sankhar’s complaint, they had set up multiple teams of 25 inspectors to investigate. His office had also written to the Bureau of Immigration for data of all those who left for Cambodia in the last two years. “We are getting calls from all over the country from the families of victims stuck there,” he said. “Tracing the financial trail is very important - it’s definitely being laundered but where is it going and what is it being used for?” While Cambodia had been on their radar for a while, following Sankhar’s complaint, they were able to take the case ahead for the first time. “He’s a brave man,” says the commissioner.

Six Months in Scam Compunds

Sankhar’s journey back home last year was more arduous than that of the 25 who returned last Friday. Through another victim he had met, he learnt that his actual agent was a man named Rajesh in his hometown. He passed on the information to his wife who went to Rajesh’s office repeatedly and told him that she would report the case to the Navy if her husband wasn’t allowed to return. In between, Sankhar managed to get the number of an Indian embassy official and called him in the hope of being rescued. Sankhar alleges, “The official AS Bhatti first blamed me for getting trapped and then told me to jump the wall and come and then he’d arrange a one-day passport.” The compound, he says, is fortified by tall walls and has armed security guards as well as CCTV cameras. “How could he tell me to jump that wall?” That evening, his employers, he says, found out he had made a call to the embassy, took him away to a dark room and assaulted him repeatedly. “I don’t remember how long it went on. I nearly lost consciousness,” he says.

About Sankhar’s allegation, Indian ambassador to Cambodia Devyani Khobragade says, “Our officers try to rescue the maximum number of Indian nationals. This particular victim might have had some miscommunication with our consular official. Because, at times, escaping from the company on their own also helps.”

Finally, under pressure from Sankhar’s wife, his agent, Rajesh, reached out to his contact in Phnom Penh, who arranged for Sankhar and a friend to be brought to the city, from where they had to make their own way home. Sankhar landed in Visakhapatnam in November.

Once he was home, Sankhar went to meet Rajesh, who tried to threaten him. Sankhar nevertheless went to the local police station but no complaint was registered, despite multiple attempts. The police hammered out a compromise, getting Rajesh to sign a bond and pay Rs 2.25 lakh, which Sankhar accepted under pressure from his family, including his wife who had suffered a miscarriage. And that was supposed to be that.

Busting the Scam

“But I couldn’t sleep at night, thinking of all those youngsters stuck in Cambodia, getting punished and tortured,” he says. He then filed a complaint through the public grievance cell, Spandana, and, in April, he got a call from the city cyber cell. “I met the commissioner and assistant commissioner and they promised me they would help. I said I don’t want anything - I just want these people to be punished.” Sankhar refused a cash reward but shows a certificate of appreciation he received from the commissioner.

Since his complaint was taken up, five agents, including Rajesh, have been arrested from Visakhapatnam and the investigation is ongoing. Earlier in May, the government formed an inter-ministerial committee focused on tackling the spike in cybercrimes emanating from Southeast Asia. On May 20, the National Investigation Agency carried out raids in locations across seven states and Union territories and arrested five people. “We also need to probe the involvement of China in this case, possibly get lookout notices and Red Corner notices issued, among others,” says the commissioner. There would also be a crackdown on agents. Earlier, in March, the Ministry of External Affairs said about 250 Indians had been rescued and repatriated from Cambodia.

“These agents are selling people dreams, making all kinds of convincing promises. There is a big labour mafia involved to supply the demand for workers,” says Irudaya Rajan, chair of the International Institute for Migration and Development. It is important to make people aware of these scams since agents would always find another door when one closes, he says. The job scam aspect of the operation also speaks of the dire unemployment crisis in India, particularly among the youth. According to the latest Periodic Labour Force Survey data, the unemployment rate for 15-29-year-olds in the January-March quarter was 17% -- Kerala, Telangana, Rajasthan and Odisha had the highest rates among states, between 23% and 32%. For all age groups, it was 6.7%.

That’s why, even for those who escaped the forced labour in Cambodia, their biggest worry continues. “The only thing I’m tense about is a job. I’m planning to go to Hyderabad to attend interviews,” says Reddy, the BSc graduate.

Sankhar, too, is looking for a job. His savings from his stint in the Navy have almost depleted and his family is unhappy he stepped forward to file a police complaint. His priority now is a job, any job, in New Zealand or Australia. “If we can go, my son’s education and future will be taken care of. And I won’t have to face these caste issues there.” One wait may have ended but the other, six years and counting, continues.

***

INTERVIEWS

‘We Have Rescued About 450 Indians’

Devyani Khobragade, Indian ambassador to Cambodia, responds to ET's queries on the rescue mission:

What is the status of the rescue operations of Indians from Cambodia? Is there an estimate of the number of Indians trapped there?

Since 2022, the Embassy of India in cooperation with the Cambodian authorities have rescued about 450 Indian nationals as of now. It is difficult to estimate how many more Indian nationals may be stuck with scamming centers in Cambodia. We are trying to ascertain the number along with Cambodian officials.

How does the Indian Embassy assist the victims?

As and when the embassy receives any request for rescue from victims or their relatives/ friends, the mission collects details and sends official letters to the Cambodian Ministry of Interior for their rescue. Once rescued, we get their travel documents prepared, help coordinate shelter and food, communicate with their families for their travel back, etc. We also help them register complaints with Cambodian authorities so they can get their exit permit.

One of the victims, B Sankhar, alleges that when he reached out to an embassy official, AS Bhatti, he first blamed him for getting trapped and then told him to jump the wall and escape. Will there be a probe?

The embassy receives several calls for rescue on a daily basis. Our officers try to rescue the maximum number of Indian nationals with a lot of hard work and dedication. This particular victim might have had some miscommunication with our consular official. Because, at times, escaping from the company on their own also helps.

‘Beijing’s Role is Very Complex

Jason Tower, country director for the Burma programme at the United States Institute of Peace and co-author of a new report, “Transnational Crime in Southeast Asia: A Growing Threat to Global Peace and Security”, speaks of the role of China in the Southeast Asian scams.

Your report highlights the role of China in the cyber scams of SE Asia. Could you explain?

We characterise Beijing's role as very complex and really being on three levels. One is a role as a perpetrator - it helped to enable all of this by allowing some of the criminal actors who have been involved for years in the casino business. They poured money back into the Belt and Road Initiative, to build up these relationships with different elements of the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese state. At the same time Beijing is also a victim. According to China's own statistics, Chinese nationals are losing billions of dollars per year in these scams and fraud losses.

It also plays a role as a source of law enforcement. The Chinese police are adopting a very strong position and cracking down on some of this in Myanmar and across other parts of the region as well. But one thing to recognise about China's role in law enforcement is that it is linking what it does overseas to its global security initiative, which is about changing global norms when it comes to the status quo. Beijing is trying to push away from the system of alliances that the United States has across the world with its political partners, including with India.

END