The Pill Police

In India, close to 300,000 deaths were attributed to antimicrobial resistance in 2019, while over 1 million deaths were associated with it. The southern state of Kerala has launched a pioneering multi-pronged, bottom-up strategy to tackle antimicrobial resistance - can it be a model for the rest of India?

9/8/20246 min read

Originally published in The Economic Times on February 12, 2024

"Why are you telling us all this? We only follow what the doctors prescribe!” When Ajith KS, a health inspector at a family health centre (FHC) in Palakkad, Kerala, and his colleagues fanned out to tell the local community about the dangers of the inappropriate use of antibiotics, this was a typical response from many residents, who bristled at their intervention.

Ozhalapathy — where the FHC is located — is a village in the shadow of the Western Ghats, closer to Tamil Nadu than the district headquarters Palakkad. Like many a border area, it has the flavours of both states — palm and coconut trees, signboards in Malayalam and Tamil and locals effortlessly switching between the two languages. The quiet village is an unlikely candidate to make news but, in January, its FHC became the second antibiotic-smart hospital in Kerala — and the country — a title accorded by the state government when 10 criteria to curb the misuse of antibiotics are met. Kakkodi FHC in Kozhikode was declared the first antibiotic-smart hospital last November.

The conversations that Ozhalapathy FHC’s doctors and officials had with local residents were part of its outreach efforts to get the antibiotic-smart tag and, according to Ajith, the most difficult. “We met with a lot of resistance. But when we asked people if they had used old prescriptions to purchase antibiotics or just took them on their own, they admitted they did. We explained why they should not,” he says. The sessions extended to schoolchildren, dairy farmers, local pharmacies and doctors in the private sector. At the spick-and-span FHC, walls have colourful posters in Malayalam, including those warning against antibiotic abuse. “Patients also have a misconception that taking antibiotics for the prescribed amount of time can be harmful and so they stop prematurely,” says Dr Ancy Samuel, medical officer at Ozhalapathy FHC and among those who steered the efforts to get the antibiotic-smart tag.

Another tough criterion to fulfil was to ensure that 95% of antibiotics prescribed at the hospital are less prone to cause antimicrobial resistance (AMR). These are categorised as “access” antibiotics by the World Health Organisation (WHO). The challenge now, says Samuel, is to ensure that these standards are maintained. “If we doctors don’t do anything to tackle anti-microbial resistance, who will?” she asks.

CAP ON CAPSULES

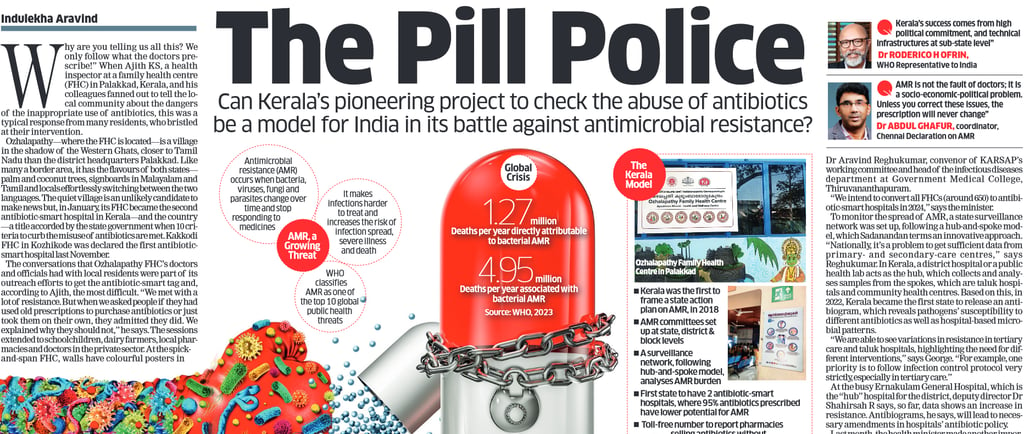

Antibiotic-smart hospitals are part of Kerala’s multi-pronged, multi-year effort to tackle AMR, which is termed as one of the top 10 threats to global public health by WHO. AMR occurs when bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites change over time and cease to respond to drugs, making infections harder to treat and increasing the chances of illness severity and even death. The crisis is fuelled by an inappropriate use of antibiotics — not just in humans but also in livestock, poultry and agriculture. It’s compounded by the inadequate development of new antibacterial treatments.

In India, close to 300,000 deaths were attributed to AMR in 2019, while over 1 million deaths were associated with AMR, according to a study by the Global Research on Antimicrobial Resistance (GRAM). “The AMR impact in India is compounded by excess (overuse/misuse) on the one hand, and lack of access to essential antimicrobials by vulnerable populations on the other. Easy, over-the-counter availability of antimicrobials, and sharing of prescriptions and medicines contribute to misuse,” says Dr Roderico H Ofrin, WHO Representative to India.

Cognisant of this growing public health threat, the Indian government formulated its first national policy on containing AMR in 2011. A national AMR surveillance network was established two years later. Then, in 2017, India released the National Action Plan on AMR. While efforts were somewhat stymied by the pandemic, the surveillance network, established by the Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR) in collaboration with the National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), continued to track AMR. According to the findings of a survey of 20 tertiary care hospitals across the country, released in January 2024, over 70% of hospitalised patients were prescribed antibiotics. And close to

60% of prescribed antibiotics had a higher potential to cause AMR. This data was not at all surprising, says Dr Abdul Ghafur, an infectious disease specialist at Apollo Hospitals, Chennai, and coordinator of the Chennai Declaration on AMR. He says AMR is a socio-economic-political problem and needs to be tackled as such. “It’s important to look at why doctors are over-prescribing antibiotics. If a doctor sees a hundred patients a day and has little time for a patient, who will go to another doctor if they do not feel better quickly, he might prescribe an antibiotic without proper examination.”

Shaffi Fazaludeen Koya, a public health expert and co-author of a paper in The Lancet, “Consumption of Systemic Antibiotics in India in 2019”, says if you compare India with similar countries, the total antibiotic use is not much higher. “But the proportional share of inappropriate use is very high,” he says.

Kerala is a huge consumer of antibiotics — we abuse it by accessing it over the counter, and doctors overprescribe it, too, says Rajeev Sadanandan, Kerala’s former additional chief secretary (health and family welfare) and currently CEO of Health Systems Transformation Platform, a Delhi-based think tank. Additionally, “Kerala is a large consumer of meat and fish, sectors where a lot of antibiotic abuse happens, leading to AMR pathogens entering the human body.” The upside is that nearly every Keralite who falls sick goes to a hospital “so the formal system can pick up cases of AMR and track it”, says Sadanandan.

ACTION PLAN

In 2018, Kerala became the first state in India to launch an AMR action plan, called KARSAP (Kerala Antimicrobial Resistance Strategic Action Plan), outlining six priority areas such as awareness and infection prevention and control. (Four other states, including Delhi, have since followed and began work on implementation.) Efforts took a backseat with the onset of the pandemic but by the end of 2021 itself, the state-level committee decided to move ahead with its plan, says Kerala Health Minister Veena George.

The implementation follows a decentralised model. The state first set up district-level AMR committees in all 14 districts, followed by block-level committees in all 191 blocks in 2023, for public outreach. “These have a monitoring and evaluation framework of what they are supposed to achieve in one, three and five years,” says Dr Aravind Reghukumar, convenor of KARSAP’s working committee and head of the infectious diseases department at Government Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram. “We intend to convert all FHCs (around 650) to antibiotic-smart hospitals in 2024,” says the minister.

To monitor the spread of AMR, a state surveillance network was set up, following a hub-and-spoke model, which Sadanandan terms an innovative approach. “Nationally, it’s a problem to get sufficient data from primary- and secondary-care centres,” says Reghukumar. In Kerala, a district hospital or a public health lab acts as the hub, which collects and analyses samples from the spokes, which are taluk hospitals and community health centres. Based on this, in 2022, Kerala became the first state to release an anti-biogram, which reveals pathogens’ susceptibility to different antibiotics as well as hospital-based microbial patterns. “We are able to see variations in resistance in tertiary

care and taluk hospitals, highlighting the need for different interventions,” says George. “For example, one priority is to follow infection control protocol very strictly, especially in tertiary care.”

At the busy Ernakulam General Hospital, which is the “hub” hospital for the district, deputy director Dr Shahirsah R says, so far, data shows an increase in resistance. Antibiograms, he says, will lead to necessary amendments in hospitals’ antibiotic policy. Last month, the health minister made another important announcement: that the state intended to stop the sale of antibiotics without prescription in 2024. A campaign is under way for this, including a toll-free number anyone can use to report a pharmacy selling antibiotics over the counter.

It is not an easy target to achieve. When this reporter approached pharmacies in the vicinity of the Ozhalapathy FHC for a strip of Azithromycin, an anti-biotic that has a higher risk of promoting AMR, two refused without a prescription. The third handed it over easily. Similarly, in Ernakulam, three pharmacies near the general hospital refused to sell Azithromycin without a prescription. At a fourth, some kilometres away, no prescription was sought.

Getting the private sector fully on board will be another challenge for Kerala. For one, corporate hospitals are not part of the state government’s surveillance network. Dr Anup Warrier, senior consultant–infectious diseases at Aster Medcity, Kochi, who represents private hospitals on the state AMR panel, says that since the extent of the crisis is well known, “there’s no added advantage in knowing more of the same thing” through their participation. Instead, he suggests making the treatment of multi drug-resistant organisms notifiable. George acknowledges that it will be an uphill task to bring private hospitals into the surveillance fold but says the government has begun talks with the Indian Medical Association to address this.

There is no dearth of challenges. Still, “Kerala’s success comes from high political commitment, and technical infrastructures at sub-state level. The AMR state committee is led by the chief minister and the health minister. In addition, there are district- and block-level AMR panels with designated focal points for institutionalising activities and providing technical leadership,” says WHO’s Ofrin.

However, Koya says Kerala’s approach might not be directly applicable to other states, where access to antibiotics is itself an issue. “Ban the sale of last-resort antibiotics, restrict those that have a higher risk of promoting resistance but make the group with the least risk available in large parts of the country,” he says. What is universally acknowledged, though, is the importance of implementing measures to address AMR, before it worsens. Says Sadanandan: “It’s already too late. If samples in Kerala are showing resistance to colistin (an antibiotic of last resort), I shudder to think what we might see in a few years.”